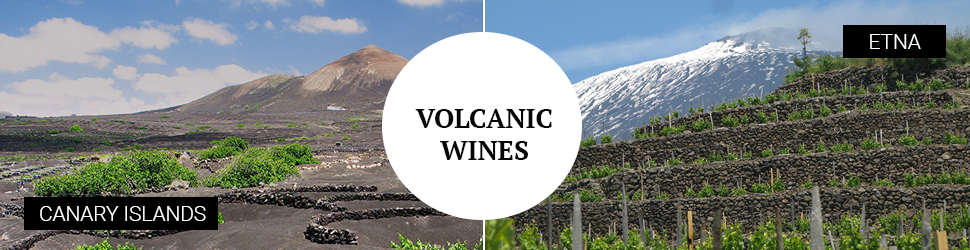

Volcanic wines

Lunar landscapes, centuries-old vines and extreme soils produce mineral wines of superlative class and great longevity

The influence of volcanos on vineyards is one of the oldest and most fascinating aspects of winemaking, offering us unique and inimitable wines. Wines from volcanic soils are enriched with an unusual salinity which gives the wines a strong minerality over time. The different origins of volcanic soils means they have different structures, acidities, and chemical make-ups, but they all have one thing in common: an abundance of mineral elements.

Historical vineyards, often ungrafted, planted over the centuries and which have survived phylloxera. But also ancestral terraces, which up to considerable altitudes, even over 600 metres, produce wines of heroic beauty. These are tough lands, black, compact, dangerous. What's their one constant? A minerality which is straightforward, decisive, with a dominant and impetuous backbone of freshness and verticality, both in whites and reds, austere, sharp. Herbs, sulphur, salts, flint: are you ready for an… explosive trip in the world of wine?

Etna

It is on the slopes of Europe's most imposing volcano that, in recent years, Sicily's most futuristic and popular wine-growing has been concentrated. Lava flows, pre-phylloxera vines and terraces up to 1000 metres above sea level are the frame of a landscape dominated by the purely volcanic soils of this wonderful terroir, rich in mineral salts and exposed to an exceptional day/night temperature range. Elegance and saline minerality are in fact the dominant characteristics of Etna wines, which some have compared, for the reds, to the finest and most subtle Pinot Noirs in the world. Etna remains, however, an area of great native grape varieties, with Nerello Mascalese, fresh and well-structured, with fragrant aromas, and Nerello Cappuccio.

Volcanic material, basalts, terraces, ungrafted saplings, craters and explosions at altitudes that reach 1000 metres: this is the scenario to which the black mascalese, king of Etna, is accustomed, and where it is the happiest. Native of the volcano, even if not necessarily originating heren, the nerello mascalese is counted among the best vines in the world as it gives a red wine clearly oriented towards elegance and not opulence and muscularity. Some liken it to pinot noir, but nerello mascalese, in addition, has a great ally: the volcano. And, obviously, vineyards of venerable age scattered in districts - especially along the northern side of Etna - which for exposure and altitude have few equals in the world. Naturally, it lends itself to important ageing both in large barrels and in barriques.

As a single variety as is usually found in the more aristocratic versions of Etna Rosso, it has a beautiful ruby colour, tending towards garnet, quite transparent, due to the presence of a modest quantity of polyphenols. The aromas are fine, with hints of red berry fruit and an interesting spicy note; the whole, on the palate, is supported by lively acidity, elegant tannins - very pungent in youth, especially from the "extreme" districts - and marked minerality, a product of the volcanic terroir. Sometimes, in the classic Etna Rosso, it is vinified in blends with nerello cappuccio, more accessible and round. It also performs well as a rosé, which is anything but sly, indeed it is biting for minerality and sapidity.

The carricante is the white grape typical of Etna that, between volcanic material and lava flows, has always been cultivated on the ancient terraces of the volcano at altitudes and exposures, especially along the south and east side, not suitable for the Mascalese red wines. It is here, on the eastern side, that the harsher climate and the considerable diurnal ranges give the wine intense perfumes and aromas. Once vinified in blends with other local white varieties, such as minnella and inzolia, today it generally competes as a single variety with Etna Bianco, revealing exceptional minerality, tension and longevity. The wine has a pale straw yellow colour. The bouquet is elegant, with delicate fragrances of orange blossom and white fruit, apple, citrus, aniseed. On the palate, it expresses a lashing acidity and a textured sapidity, clearly volcanic, with mineral returns of flint. The structure is never overwhelming, as a top-class mountain wine, it lends itself both to aging in steel only, to enhance freshness and fragrance, and to the movement to wood, if one prefers to privilege complexity and softness.

Canary Islands

A moon-like landscape between Africa, the Atlantic and Europe. This is the scenario that greets the Canarian wine enthusiast: an area that has yet to be discovered on an international level but which holds a treasure trove of oenological jewels that is unique in the world. Very old vines, purely island types, on soils that were once arid and inaccessible, and today, especially after the eruption of the Timanfaya volcano in 1730-36, covered by a lava layer of lapilli that has made them an earthly paradise for quality viticulture.

On Lanzarote, the bush vines, often free-standing because phylloxera does not attach itself to them, are protected from the Atlantic currents in basins dug out of the black soil and surrounded by semi-circular dry stone walls. To walk along La Geria, Lanzarote's picturesque wine route, is to immerse oneself in this lunar landscape as far as the eye can see, seemingly designed by an alien geometry. While Lanzarote retains this rustic vein - up until a few decades ago, the harvest was carried out on dromedaries - Tenerife appears more evolved and receptive, thanks also to modern tourism: at the foot of Teide (3715 metres), the main wine denominations of the Canary Islands are developed.

Mineral salinity, sulphurous, and oceanic salinity, marine. Large day/night temperature ranges. Amazing altitudes. Manual, hard, impervious, heroic work. Small and tiny producers who extract every drop of must from two-hundred-year-old vines. The local Malvasia (dry but also sweet or amabile) emerges with mineral power and incredible aromatic qualities, and together with Palomino and Moscato d'Alessandria it produces the bulk of the native whites. Among the black grapes, the Listán Negro stands out, which produces delicate reds and rosé wines, but which is now being experimented with in ageing or blended with Shiraz to obtain greater body and opulence.

Tokaj

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the Hungarian district of Tokaj and its neighbouring municipalities have been producing the world's greatest wines for centuries. This is demonstrated by a thousand-year history of success, at least since the Magyars defended their ancient vineyards from Mongol and Turkish invasions, taking refuge in picturesque cellars dug into the volcanic rock of these lands (to date there are about 13 km of excavations!).

This is simply because the rounded mountains of Tokaj, which border the immense Hungarian plain, are nothing more than ancient extinct volcanoes. Exported since the 16th century, Tokaj wines were considered the noblest in Europe until the 19th century, so much so that they appeared at every royal banquet and were defined as the "wine of kings" by Louis XIV of France. In 1737 they were first classified geographically, the first case of wine legislation in the world.

In its typical version, called Aszú, Tokaji is a sweet wine made from mouldy grapes by mixing fresh must and must from botrytized grapes in varying quantities (called Puttonyos). This is followed by very slow fermentation and long ageing in 136-litre oak barrels. The pungent continental microclimate, very windy and with excellent day/night temperature variations, and the volcanic soil rich in potassium, salts, sands and clays make this wine unique in the world: concentrated, dense, structured (over 300 g/l of residual sugar is absolutely the norm), but also incredibly sapid, mineral, with a fixed acidity that easily reaches double that of any ordinary wine.

The secret of Tokaji lies precisely in combining the geographical characteristics of the world's greatest botrytised wines - a breezy, temperate afternoon climate that sweeps away the fine, damp morning mist that forms at the confluence of the Tisza river (Tisza) and the Bodrog stream - with the virtues of a volcanic terroir.

This explains why, together with the success of classic Tokaji, which is now being reborn after Soviet collectivisation, thanks also to a reinterpretation of it that is less cloying and oxidative than in the past, we are witnessing a great revival of dry Tokaji. The main vine, the native Furmint, which is resistant to cold and very well suited to botrytis, is also capable of developing notable mineral aromas of hydrocarbons and flint, transforming itself into white wines (dry or amabile from late harvests) of extraordinary longevity.

Soave and upper Piedmont: ancient volcanoes of northern Italy

Among the best Italian whites, Soave wines express the typicity of volcanic wines from the north created from the wonderful Garganega grapes. Soave is a marvellous region with gentle hillsides hiding extinct craters and a checkered volcanic landscape made up of chalky, alluvial, sandy, and basaltic soils. Every corner of the appellation, almost every hillside, dedicated to winemaking since the early Middle Ages (local wines were first ‘regulated’ in the Statuto Ezzeliniano document back in 1228) displays its own particular character, all coming together in the extraordinary Soave Classico area located between Soave and Monteforte d'Alpone.

The Garganega variety is not known as an especially aromatic grape but it does offer a range of fragrant gifts, such as the elegance of white flowers, notes of almonds, and perhaps a hint of citrus fruit. These characteristics make for persistent, never-ending wines but it also means they are excellent for laying down. Top wines from Soave can be kept for over ten years. A late-ripening variety, Garganega has plenty of acidity and provides wines with a wonderful balance between structure – generally agile and fluid – and amiability. Wine-production regulations allow Garganega to be blended with Trebbiano di Soave, a variety more usually associated with the Lugana appellation, and even with some international grapes like Chardonnay.

Cultivated in Nebbiolo well before the Langhe, in the last hundred years Northern Piedmont has lost about 90% of its wine heritage. The vineyards now appear to be clinging to heroic slopes, and appear suddenly within clearings in the dense forests of this area. Here, amongst the provinces of Novara, Vercelli and Biella, Nebbiolo from Boca, Ghemme, Gattinara, Bramaterra, Lessona takes on an unmistakable character. Less structured than that of the Langhe, it gains enormously in finesse and aromatic depth, giving, thanks to the strong minerality, which is sometimes ferrous, an incredible longevity.

This is due to the exposures, the considerable altitude and the tense and foggy climate, but above all the soils. Although fragmented in many small denominations, the district of North Piedmont is almost entirely on volcanic soils deriving from the prehistoric explosion of a crater that has littered the soil with a strong porphyry component. Poor and mineral soils, therefore great wines.

From Vesuvius to Vulture: the volcanoes of the South and their wines

From the Castelli Romani, just south of the capital, to the Vulture massif in the highlands of Basilicata, the whole of central and southern Italy is one vast volcanic area. And a large part of this area is dedicated to viticulture.

The Frascati, with its splendid volcanic crus in the countryside of the Roman otium, is today among the greatest Italian whites, vertical, mineral, but also warm with its beautiful aromaticity of the native Malvasia Puntinata. And then the Cesanese. Once a rough cutting wine, today the great Frascati red excels both in its youthful rustic brio and in the deep complexity that it acquires over the years.

The secret of Campania's excellence, in addition to its history and numerous varieties, lies in the soils and climates. Few regions like this can boast so many volcanic areas: natural amphitheatres that, as we know, offer interesting wines for minerality and longevity. As for the climate, Campania comes out on top for diversification in this area too: in fact, we can appreciate the Mediterranean climate of the coast, that of the inland, almost alpine-like, with day/night temperature variations that are splendidly beneficial to the aromatic characteristics of the wines. Towards the Mediterranean coast, the falanghina finds its home in an important volcanic area: the Campi Flegrei. And here, of course, it becomes more subtle, tense, sometimes terse in its youth, of exuberant minerality. And this is perhaps the greatest falanghina, capable of some years of ageing in the bottle. The Campi Flegrei, an area of volcanic fumaroles around Pozzuoli, also offer another great native of Campania: the piedirosso. A grape of contained structure, good aromas which is easy to drink, and which along with the Aglianico is one of the most traditional grapes of the region.

Again among the whites, biancolella, native grape of the island of Ischia, has reached sublime levels. Especially in the heroic crus located in the south-western part of the island, the biancolella, cultivated on rocks of greenish mineral of volcanic origin, expresses an olfactory complexity and richness in extract now known internationally. From Naples to the Sorrento Peninsula, we meet the wines of Vesuvius. A naturally volcanic area, it produces both whites - in particular from coda di volpe grapes, simple but pleasant and with good acidity - and reds, from the typical blend of aglianico and piedirosso. The Lacryma Christi del Vesuvio, white or red, comes from the most selected vineyards, on which sometimes ancient ungrafted vines survive.

The testimonies of Horace, who was from Venosa, and Pliny, attest that already in ancient times the propulsive and qualitative centre of Lucanian viticulture was the northern part of the region, towards Vulture: a gigantic extinct volcano that hosts the most suitable area. Around Vulture, snow-covered in winter and with vines that reach over 600 meters above sea level, towns like Melfi, Rionero and Barile are considered the real crus of the local Aglianico. Aglianico is a difficult grape, here as in Irpinia, and is nervous and lively in its youth, but in the long aging it gives extraordinary sensations for structure, elegance, subtlety and class of tannin. The volcanic soils of this area, with tufaceous and clayey-calcareous inserts, are an incredibly perfect setting for the production of an Aglianico with a unique personality, perhaps the largest and most valued red in the South. At the same time, the ancient cellars of the Sheshë in Barile, excavated five centuries ago by the arbëreshë, are being recovered and can still be visited today with their fascinating black-lava-stone walls.

Pantelleria and the Aeolian Islands: the other volcanic Sicily

Some of Sicily's smaller islands, such as Pantelleria and the Aeolian Islands, are of volcanic origin, as can be seen from the geological layout of the territory, the craters and the black beaches. It is no coincidence that they are the most important wine-producing areas outside the “mainland”.

The nerellis (mascalese and cappuccio) are the most representative reds of the Aeolian Islands, although between Salina and Lipari the typical local malvasia excels, both dry, of great minerality to balance the subtle aroma, and in the passito version, protected by the Malvasia delle Lipari DOC, characterised by notes of dehydrated apricot, delicately salty, pleasantly ethereal and spicy, with sulphurous puffs. Compared to the malvasia family, the Aeolian Islands family seems to have a different story. Less aromatic, it supposedly reached the archipelago in ancient times, around 588 B.C., thanks to the Greeks who colonised Sicily. According to some, it is related to the greco with which the Greco di Bianco is produced in Calabria. And, in fact, even malvasia delle Lipari finds its highest expression in the passito version, protected by the DOC of the same name. A wine that combines the concentration of sugar and the characteristic fragrances of orange peel, orange blossom, candied fruit, sweet date, caramel with a splendid mineral texture typical of the marine and volcanic area. It is vinified, however, and with excellent results, even dry, giving a clear white wine with a good structure, explicitly mineral, sometimes with notes of flint, perfect for simple seafood lunches but also suitable for a little aging.

The Pantelleria DOC, which occupies the volcanic island off the coast of Agrigento, deserves a special mention. Here, on land hollowed out by the winds and craters, or on heroic terraces overlooking the sea, zibibbo is cultivated in ancient bush-trained saplings which are often free standing. A type of muscatel with a slight aromaticity, the zibibbo is vinified dry for a white wine of extreme iodine mineral content, or sweet, both in late harvest and after withering: it is the Passito di Pantelleria, a UNESCO World Heritage wine. Whipped by the wind and the sun, the bunches wither for a variable period depending on the style of the producer. According to an ancient technique, some vinify the passito using a balance of wine from fresh grapes to ensure the right acidity to the product. Then the aging, which can take place in steel or wood and can last even a decade, sometimes with moderately oxidative and decidedly salty results to accompany the characteristic note of dried apricot which, with its great taste-olfactory concentration, is the trademark of this flagship of Italian wine.